- Jobs

- Open Calls

- Events

- Learning

- More

- SUBMIT

Amy Jackson

Country:

City:

Newspapers

I remember when I was five years old, (a lover of art), I had decided to paint my dad, (lover of wildlife), a picture of a squirrel.

Recounting my school teacher’s wise guidance to ‘put newspaper down’ before attempting to paint, I diligently laid old sheets of last weeks’ newspapers onto our 1970’s designer table. When my dad arrived home I was very excited to show him my picture - it was holding a little acorn, standing on some grass, not a care in the world.

Taking one look at the picture he began to scream at me and chase me up the stairs. I hid in my room, sat on the floor rocking with my hands over my ears whilst he banged on the door asking what the hell I had done.

Hours later I came to realise that he was annoyed that I’d got paint on his old newspapers.

Years later I learned he mentally ill.

Decades later, he was diagnosed with the world’s worst recorded case of hoarding, OCD and asperger syndrome. We had lost our family home, every penny he’d ever had and our sanity simply from being in close proximity to his madness.

Yet despite all of the debts and an ability to hold down a job - for most of his life he had every UK newspaper delivered to our house daily. It was as though our family home stood beneath paper rain, flooded by the past, drowned in darkness.

I always speculated that newspapers were somehow comforting to him, a way of hoarding and preserving memories. A fabric of existence, proof that time had passed. Reliable in their repetition, daily delivery, rarely changing from decade to decade.

I began to steal the papers, cutting every ‘a’ out of some, snipping 30,000 circles out of others (only to stitch them back in again), and moulding others into newspaper bricks (ready to build my own house).

This documentation and repetition of madness became a method of coping and more importantly a way of demonstrating the scale of the problem to those around me through my art practice.

I hope these images tell the story through the work which I have made and I hope one day I will be able to make sense of it all. One day when he is gone and only the newspapers are left, their value will once again be great.

Instagram:

Twitter:

A glimpse into a dark cavity between the 100's of 1,000's of newspapers filling my family home in Leeds in 2005.

A shot of one week's worth of my father's newspaper delivery stacked in our hallway in Leeds, 2005. Often it was very difficult to get in and out of the house and my mother was often worried about my young nieces and nephews being crushed by the weight of them.

Struggling with my own mental health when I began university, I started cutting every 'a' out of my dad's newspapers. This image depicts a photograph of a newspaper missing every 'a'.

A man’s real possession is his memory. In nothing else he is rich. In nothing else he is poor.

Every ‘a’ seeks to explore the ways in which obsessive compulsive behaviours can develop in those seeking to exert control over intangible treasures such as time and memory.

Every ‘a’ is part of an extensive body of work called The Newspaper Collection. 26 free identical newspapers were collected, each letter was painstakingly extracted from each until separate jars of ‘a’s, ‘b’s, ‘c’s and so on, filled up. An installation examining just the letters and the newspapers was exhibited in Modern Art Oxford.

The hollow newspapers were later photographed by the artist and abstract images of infinite tunnels and starry nights were created. The collection of photographs became works in their own right of which there are 26 one-off prints, each with their own name.

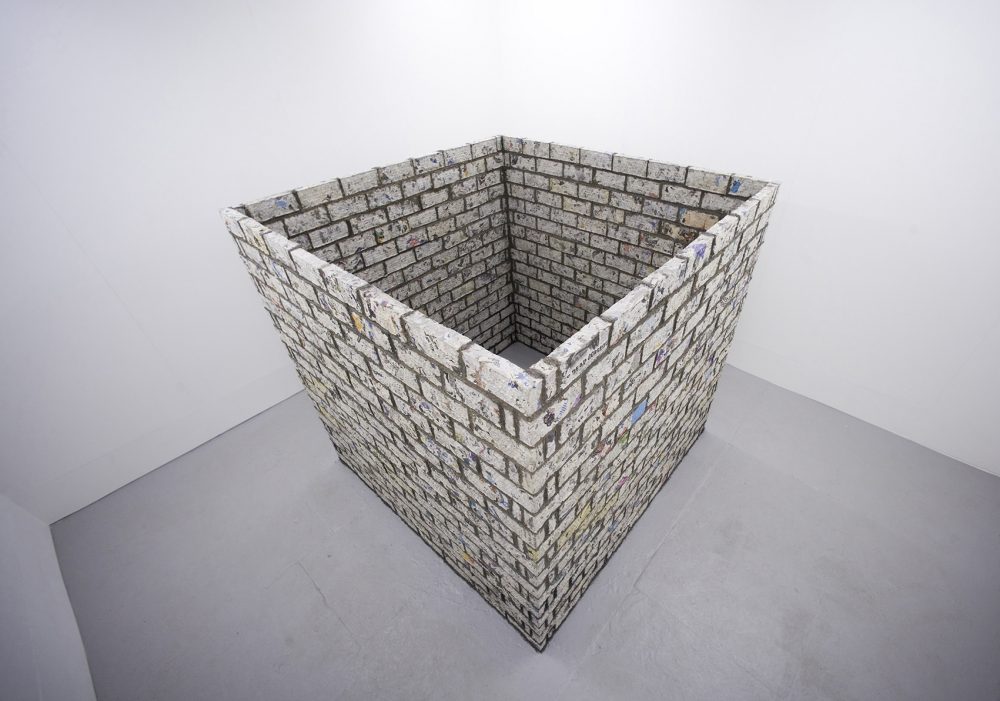

This is one of my art pieces entitled house which I made about my father's mental health (later sold to the Warneford Hospital, Oxford, UK). It was made from 579 newspapers, dated 21st September 2006 - 27th April 2008, ‘mortar’ and was 5 foot 8 inches cubed.

“Man is separated from the past (even from teh past only a few seconds ago) by two forces that go instantly to work and cooperate: the force of forgetting (which erases) and the force of memory (which transforms). Beyond the slender margin of the incontestable (there is no doubt that Napoleon lost the battle of Waterloo), stretches an infinite realm: the realm of the approximate, the invented, the deformed, the simplistic, the exaggerated, the misinformed, an infinite realm of non-truths that copulate, multiply like rats, and become immortal.” Milan Kundera

The senses provide an infinite pulp of information. This is too much for indiscriminate internalisation, and so day-by-day we systemise it, categorising, ordering and patterning it into blocks of time. In the process we mould it into a certain shape, and store it in the recesses of our mind, our memory. The resulting artifice is at once simple in form yet complex in content; minimal and maximal. We can access it, but at the same time, it encloses us, and forms the space in which we live and move. It protects us, yet also entombs us; it is a home without windows or doors.

(house was a sculpture created by Amy Jackson using The Times newspaper, which she 'stole' from her father's collection of newspapers. The papers, filling the house, multiplying daily, like pillars of time became a yellowing prison, impossible to escape. house seeks to question the value we place on objects and their meaning).

This image a close up of my piece 'Stitch' where I cut over 30,000 holes from an antique Times Newspaper Compendium dated from the 1800's. The individual circles were displayed all over my family home, demonstrating the insanity of the gesture and later restitched in place by hand with a needle and thread.